From the ‘battle of Bakhmut’ to the ‘march of justice’: Prigozhin’s audio files, transcribed

it is possible to use open source tools for transcribing audio messages locally and the quality is reasonably good also in the case of messages such as Prigozhin’s filled with slang and expletives (adding automatic translation, the contents are still mostly readable, but the quality is noticeably degraded)

exploring mixed-media contents published on Telegram channels may be challenging, but feasible

just looking at changes in the frequency of posting it is possible to observe Prigozhin’s radicalisation journey

a full dataset with all of Prigozhin’s audio messages transcribed is available for download, or to consult in a single page in Russian or with automatic translation in English

Context

Context

As the Kremlin tightened its control of narratives and news that feature in mainstream media, Telegram has gained a significant role as the venue where Russian citizens of different persuasions look for information and opinions. Indeed, Telegram has remained one of the few uncensored on-line spaces (another one being YouTube) that can be freely accessed from Russia without having to rely on VPNs or other censorship circumvention techniques.

In many ways, mainstream media and Telegram channels seem to be two parallel information spaces, with debates and news that are dominant on Telegram (where re-posts among popular channels are common) may be completely ignored by major broadcast media. Indeed, the invisible line tightly separating these spaces is punctured only occasionally, and figures that are prominent on Telegram or even Western discourse about the war would be almost unknown to people who relied strictly on federal TV channels to get their news.

In the full web archive of news of Russia’s Pervy Kanal, there is literally only a handful of mentions of Evgeny Prigozhin until June 2023, all of them related to questions Putin has received in interviews in earlier years and that refer to Prigozhin’s involvement with the so-called “troll factory” based in Saint Petersburg. But there is no reference to his role in Ukraine, not even during the months-long battle of Bakhmut; not even a hint or passing reference to the growing tensions between Prigozhin and the Ministry of Defence that marked the months preceding Prigozhin’s mutiny.1 And yet, most respondents to opinion polls seemed to know enough about Prigozhin to have an opinion about him. For a brief period before the mutiny, he was one of the public figures most frequently mentioned approvingly by survey respondents, at one point even the most frequently mentioned after president Putin, even if this is likely more the result of a relatively small number of strong supporters rather than of widespread support.

Either way, it seems clear that contents spread through Telegram reach a substantial part of the Russian population. Telegram channels is also the primary way used by figures such as Prigozhin to share their opinions and messages. In brief, there is plenty of good reasons for scholars interested in the spread of information and narratives related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to dedicate some attention to Russian-language Telegram channels. Indeed, there have been some efforts in this space that outline the prevalence of pro-Kremlin channels on Telegram.2

Rather than dealing with a large number of Telegram channels and their interactions, this post focuses on the task of analysing the contents published by a single figure - Evgeny Prigozhin. It is an interesting case not only because of its obvious relevance in relation to the war, but also technically, because of the variety of formats it employs as well as the peculiarity of each format for conveying different messages. Indeed, as will become apparent by the end of this post, in the case of Prigozhin the switch from written text to audio messages has effectively characterised the radicalisation journey of Prigozhin’s public persona.

Step 0: Understanding Prigozhin’s presence on Telegram

How does Prigozhin’s communication work? In brief, Prigozhin’s press service actively responds via Telegram to questions received by journalists via email. Questions are mostly posted as screenshots, while responses have been increasingly posted as audio messages. Other posts may be in video format, including clips with prisoners, combat images, or video clips with Prigozhin’s voice.

There is an additional difficulty: Prigozhin’s communication is surprisingly orderered in some respects, messy in others.

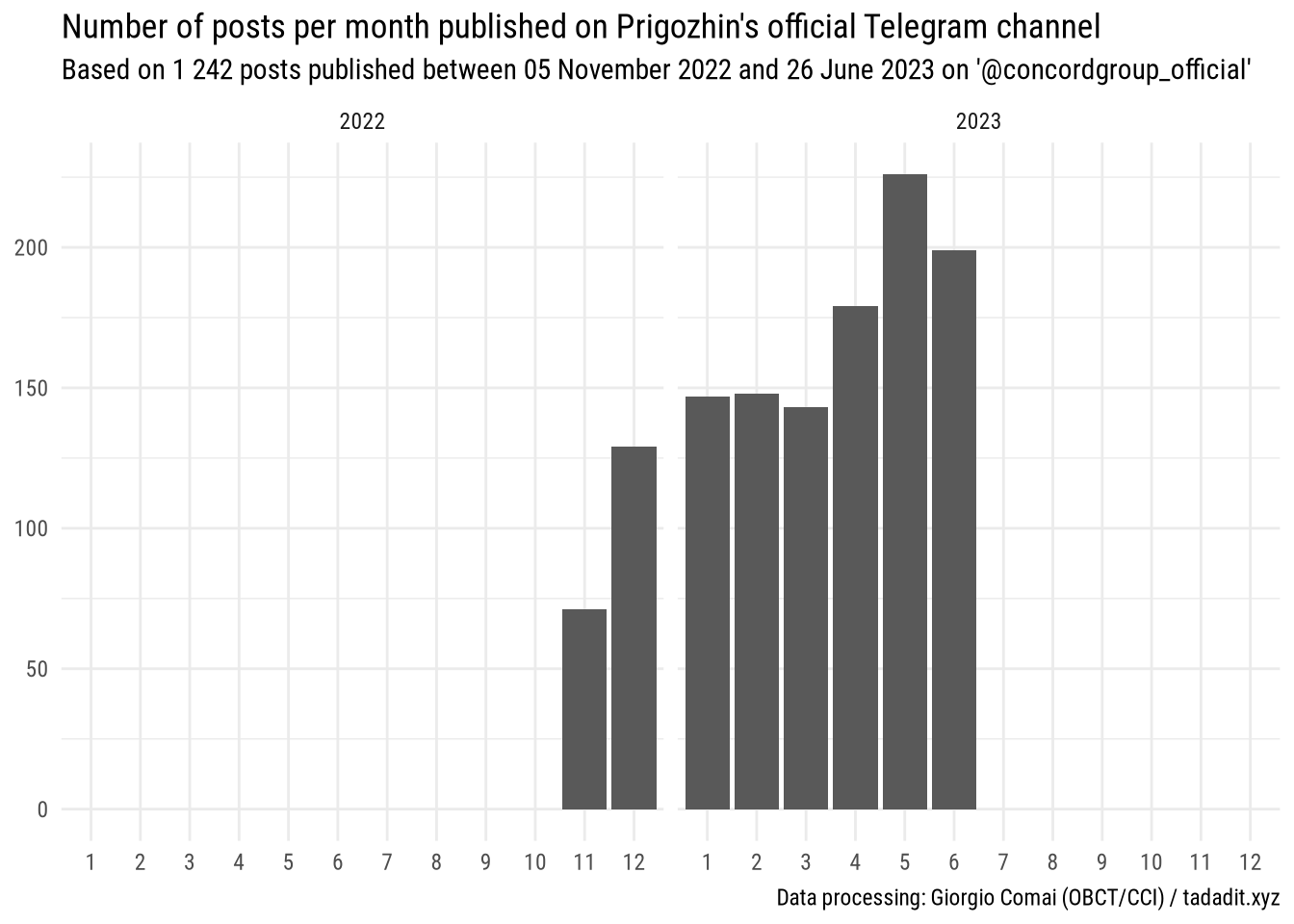

Prigozhin has one main official Telegram channel that he uses for “official” communication, which is called “Prigozhin’s press office”, and has the Telegram handle @concordgroup_official, “Concord Group” being the name of the holding company that controls Prigozhin’s various businesses. At the time of this writing in August 2023, the channel has almost 1 million 250 thousands subscribers.

Let’s start with the surprisingly ordered part: (almost) each message starts with a numeric identifier, in a format such as the following: “#903 Запрос от редакции газеты…” (“#903 Question from…”). The post on 26 June in which Prigozhin offers some “clarifications” on the mutiny which has by now over 4 million views starts with “#1851 We publish the response of Evgeny Prigozhin…”. As of August 2023, no other message has been posted on this channel. So in principle, everything looks nice and clear: there are so far 1851 statements by Prigozhin.

Now, let’s move on to the messy part.

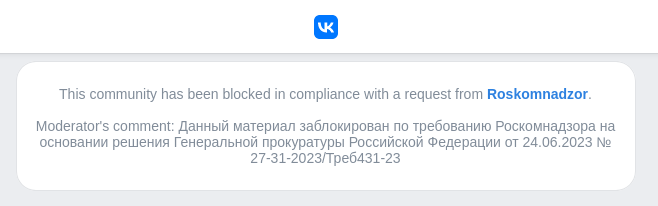

First, there is no official website to take as a point of reference. The official Telegram channel’s bio includes a link to the official page on Vkontakte, a popular Russian service similar to Facebook. However, the page on VKontakte has been blocked after the mutiny by request of the Russian authorities and appears to be still blocked with the following notice:

The Telegram channel itself was opened only in November 2022, with message #897. Previous messages were probably published first on VKontakte (now not reachable), and presumably reposted from there in other Telegram channels.

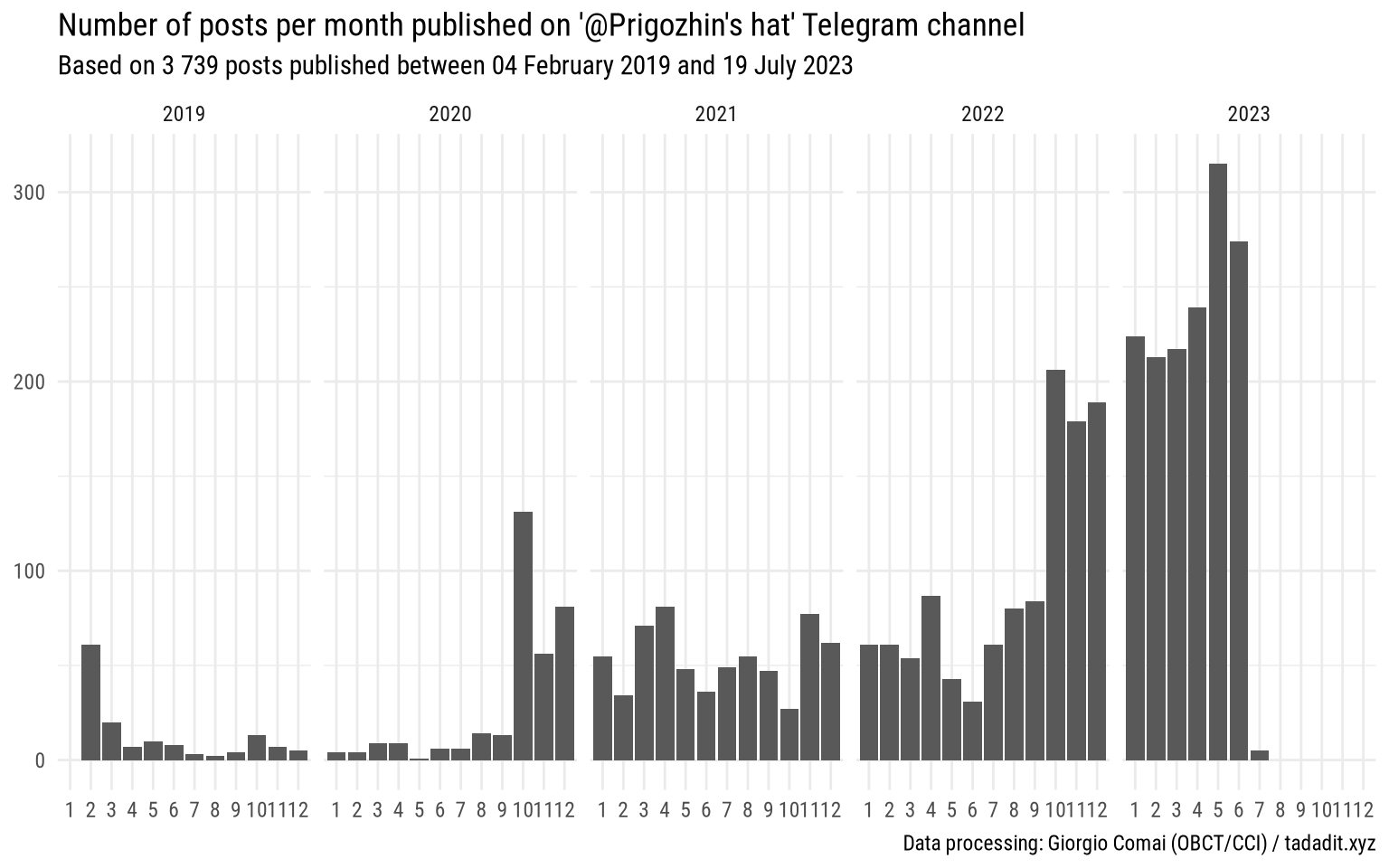

Telegram channel “Prigozhin’s hat”, for example, has over 500.000 subscribers and was opened in February 2019. Even earlier posts look exactly the same as ones published on the official channel, and it appears they are effectively just (partially automated) re-posts. However, unfortunately, they do not include the same numeric id used in official posts. Besides, there are some more contents published on Prigozhin’s hat that do not feature on the official channel, including a few posts published after the mutiny. These are mostly forwarded from other Prigozhin-related channels such as “Razgruzka Vagnera” or “SOMB - ’Tourists in Africa” (related to Wagner’s presence in Africa). On 21 August 2023, for example, a new video post by Prigozhin aimed at recruiting personnel for Wagner missions in Africa appeared; an audio message posted as a response to a question supposedly by an African media posted as a screenshot in French has appeared on the same day. A new chapter in Prigozhin’s communication efforts may be beginning.

“Prigozhin’s hat” may at this stage be the easiest source for earlier posts issued by Prigozhin (as well as possibly for the post-mutiny period)^[Others sources may well be available; I welcome suggestions about full archives if available.], while @concordgroup_official is the most consistent source for recent months. As will appear from the following sections, it is really starting from early 2023 the Prigozhin stepped-up his virulent rhetoric expressed through audio messages, so in many respects it makes sense to focus on more recent contents and look at previous contents only as a term of reference.

To summarise, contents posted by Prigozhin’s press service are a combination of:

- text messages

- text included as screenshots of emails (and, occasionally, documents)

- audio messages

- video clips of different length and format

How do we turn these into something that can be searched and analysed?

Step 1: Get the data out of Telegram

From Telegram Desktop, it easy to export the full archive of Telegram channel in machine-readable format, exporting all posts with metadata as a single .json file, as well as all images and files in dedicated subfolders.

First, let’s have a look at some basic information about the dataset we have:

Earliest post: 2022-11-05

Latest post: 2023-06-26

Total number of posts: 1 242

Total number of audio files: 408

Earliest post with audio file: 2022-12-26

Latest post with audio file: 2023-06-26

Total duration of audio files: 29628s (~8.23 hours)

Average duration of audio files (in seconds): 73

Median duration of audio files (in seconds): 51

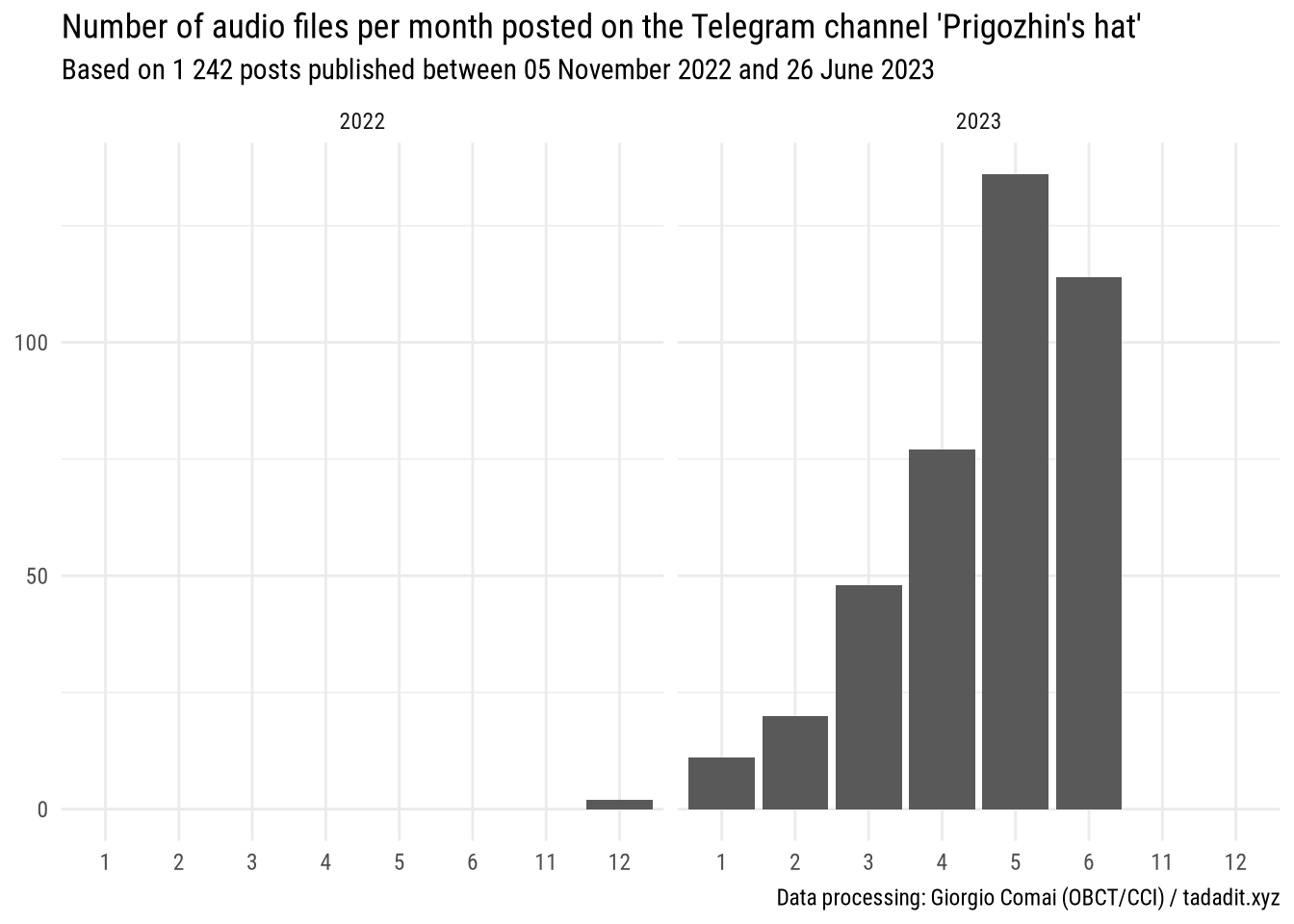

For reference, it may be useful to look at “Prigozhin’s hat” to look at the frequency of posts in earlier months.

It appears there is a distinct crescendo in the number of posts published by this channel (presumably reflecting Prigozhin’s overall post frequency also on its currently unavailable official channels), from just a handful of posts per month until September 2020, then mostly between 40 and 80 monthly posts until September 2022, going up to more than 200 post per month until the end of June 2023, when the channel fell silent post-Mutiny, after averaging close to 10 posts per day in the previous weeks

Even these basic descriptive statistics reflect some of the things we know about Prigozhin: the big increase in posts in October 2022 can easily be explained by the fact that it is only then, more precisely on 26 September 2022, that Prigozhin publicly admitted its ties to Wagner. Two days earlier, on 23 September 2020, the US treasury significantly expanded its sanctions against entities linked to Prigozhin, which may be related to him taking a more public role.

Since the very beginning of its online presence, Prigozhin’s press team published the questions it received as a screenshot, and added Prigozhin’s own reply either in the text of the message or as an additional screenshot with text. As emerges from the following graph, it is basically only starting with 2023 that Prigozhin started to respond with audio messages - often, angry rants - that quickly became a trademark element of its communication.

As a consequence, since the focus of this post is Prigozhin’s audio messages and its rhetoric escalation in recent months, for the rest of this post I will mostly stick to Prigozhin’s official channel: as no audio message was posted before the new channel has been opened, key contents should all be there.

Step 2: An overview of the kind of posts published

Posts published on the official Telegram channel of the Prigozhin’s press service as well as on “Prigozhin’s hat” Telegram channel including older posts by Prigozhin are mostly based on a combination of formats; sometimes the contents are repeated in more than one format, sometimes they are not.

For example, this post shows a question asked by a media organisation as a screenshot:

Conveniently, this is accompanied by another post that includes both the question and the answer given in both textual and audio format:

In this case, everything seems easy: we can in principle ignore both the screenshotted picture and the audio-file, as the very same contents are presented also in textual format.

But then, in other occasions there are only audio-files or voice messages with no context whatsoever. This was the case, for example, for most messages posted during the mutiny on 24 June, including the one that announced its end:

In others still, the content of the question previously-screenshotted is transcribed, but Prigozhin’s comments are conveyed only in audio format.

Finally, there are occasional posts including some documents or video files:

Video files often include spoken comments, or depict meetings. They are only very occasionally central to Prigozhin’s communication, and even when they are, mostly not for the spoken content. Video files should not be dismissed, however, and they may actually be an important part of the communication of other Telegram channels, all the way from Strelkov to the “military bloggers” who produce video contents. In the rest of this post, I will leave out video clips, both for facilitating consistency in the processing of results and because including them introduces further ethical questions (they include, among other things, the voice of Ukrainians prisoners of war).

In the following steps, I will proceed with turning images into text (only briefly) and then really focus on turning audio messages into text format that can be searched and processed further.

Step 3: OCR images

As screenshots of text have become less common on Prigozhin’s official channel in recent months, and as they are broadly a format less frequently found on Telegram in comparison to video and audio files, I will go through the image part quickly, and then focus more on audio messages. Given the prevalence of textual screenshots in earlier posts, this section will take messages from “Prigozhin’s hat” Telegram channel, rather than the official one; the vast majority of posts are exactly the same on both channels, but, as mentioned before, “Prigozhin’s hat” has a lot more of the early posts.

OCR techniques to recognised text from images are well established. In this specific case, the quality of results is hindered mainly by two aspects:

- low resolution of the images

- the fact that many of these are screenshots of emails, and they may include some email metadata at the top, or some signature text at the bottom of the email

- the fact that there are sometimes more than one language in the same image, either because there’s some clutter in the email screenshots, or because questions are asked in English and the response given in Russian (in the vast majority of cases, however, both questions and answers are given in Russian)

The following is a quick attempt to extract the text of the images via OCR, with no particular effort dedicated to polishing the results. Even so, the process allows to conduct quick searches among transcribed text. For example, if you look for “Wagner” (“Вагнер”) in the search box for the text_photo column, only posts where “Wagner” is mentioned in the screenshotted text will be kept. For the records, this shows that out of 1 839 posts with valid text extracted from the images, 491 mention “Wagner”, all the way from the early days of the channel back in 2019 when Prigozhin was still vehemently denying any association with it.

Some information about the following table:

- the table includes all posts that have attached a photo from where seemingly meaningful text could be automatically extracted

- the text has been automatically extracted with OCR with

tesseract, setting the language as Russian (hence, the glaring inaccuracies where the images include contents in other languages) - if the post has attached more than one image, the text for each image is included in a separate row; the embedded post is always the same and it may not be immediately obvious that it includes more than one picture

- very often, the response to the question is given in a separate post: clicking through the embedded post, and then clicking on “context” may be helpful in finding more details in the posts immediately preceding or following any given post.

For more detailed analysis, and depending on the type of analysis, this would likely require some more polishing efforts. Also, as the same textual content is often repeated both in the screenshotted image and as text in the original post, this may lead to extensive duplication of contents. On the other hand, if one is not into word frequency analysis but just into more effective ways to search through all contents of the channel, this may well already be of use.

Step 4: Speech-to-text of audio and video attachments

One of the most distinguishable features of Prigozhin’s mutiny for external observers was just how much it was communicated through Telegram posts, mostly bare audio messages of Prigozhin’s raucous voice: the mutiny was launched with an audio message and its end was declared in the same way. Indeed, audio messages had become an increasingly central component of Prigozhin’s approach to communication, as it was perhaps most fitting to his harsh and increasingly unhinged comments towards Russia’s military leadership and the Ministry of Defence.

Many of these audio messages have been transcribed and posted as text in the same post that has the audio file, or in a separate message posted immediately sooner or later. However, others were not: these may be longer audio messages, messages with more vulgar or explicit expressions, as well as most of the messages posted during the mutiny on 24 June 2023.

Due to the molteplicity of formats employed, systematically harmonising these contents through consistent deduplication may be challenging. But the first step in that direction surely involves transcribing these audio messages.

There are a variety of online services that offer speech-to-text as a service for a fee. Depending on the use case, the budget available, and the amount of audio to be transcribed they may be a valid option. Processing data locally introduces other constraints - mostly, computing time and resources - but allows for reproducibility, and makes irrelevant a set of additional concerns that may emerge by relying on third parties, including questions such as:

- “are third-party vendors fine with me using their services for transcribing profanities by an alleged war criminal?”

- especially for those working on violent extremism or terrorism, “will sending a bunch of extremist materials get me into trouble”?

- if I am transcribing non-public and potentially sensitive contents, is it fine ethically to send them through a third-party, perhaps one based in different jurisdiction?

Terms of service may offer some assurances, but processing data offline makes such points moot.

Speech-to-text: some details on the technicalities

Some details about the technicalities: uninterested readers may skip to the next section.

To transcribe these audio-messages I used OpenAI’s “Whisper” Automatic Speech Recognition model. For ease of use and consistency with my R-based workflow, I did this through the audio.whisper R package, which is a wrapper around the whisper.cpp C++ library. This may sound convoluted, but it is rather straightforward in practice, as it deals with many of that complexities that users of libraries based on machine-learning models often encounter. Especially for users with poweful GPUs, this may lead to significant inefficiency. For others, this should really be just about as efficient as running the original library if audio.whisper is installed with the right flags (see the package’s readme) and if the software is run naively, with no specific customisation or optimisations. Notice that whisper can process audio using one of a set of models ranging from “tiny” to “large”, with “tiny” being the quickest and least accurate and “large” the slowest but more accurate. Notice that if you use the original library, you have a decent GPU and set it up correctly, you can have very noticeable speed boosts, if the model fits into the VRAM of your GPU. Unless you really care about these things, even higher-end laptops mostly have GPUs with 4GB of VRAM or less, meaning you would probably be able to run only the “small” model (“large” requires ~10 GB of VRAM, see the project’s repository for details).

After some testing, I found that when the quality of the audio is very good, e.g. a TV news segment where words are spelled out clearly, even smaller models perform relatively well, and “medium” is already almost flawless. However, with audio messages filled with slang and often with less than ideal audio quality such as the one posted by Prigozhin, the “large” model seems to be really needed to get reasonably reliable results. It is however, time consuming, as transcribing a minute of audio using the large language model on a modern laptop takes a few minutes (it would be much quicker with enough GPU vRAM for the large model, but, again, most consumer laptops won’t have the right hardware); transcribing all of Prigozhin’s audio files implies quite a few days of processing.

Before proceeding with transcribing, here are some summary statistics about what we’re looking at.

Summary statistics about Prigozhin’s audio and video posts

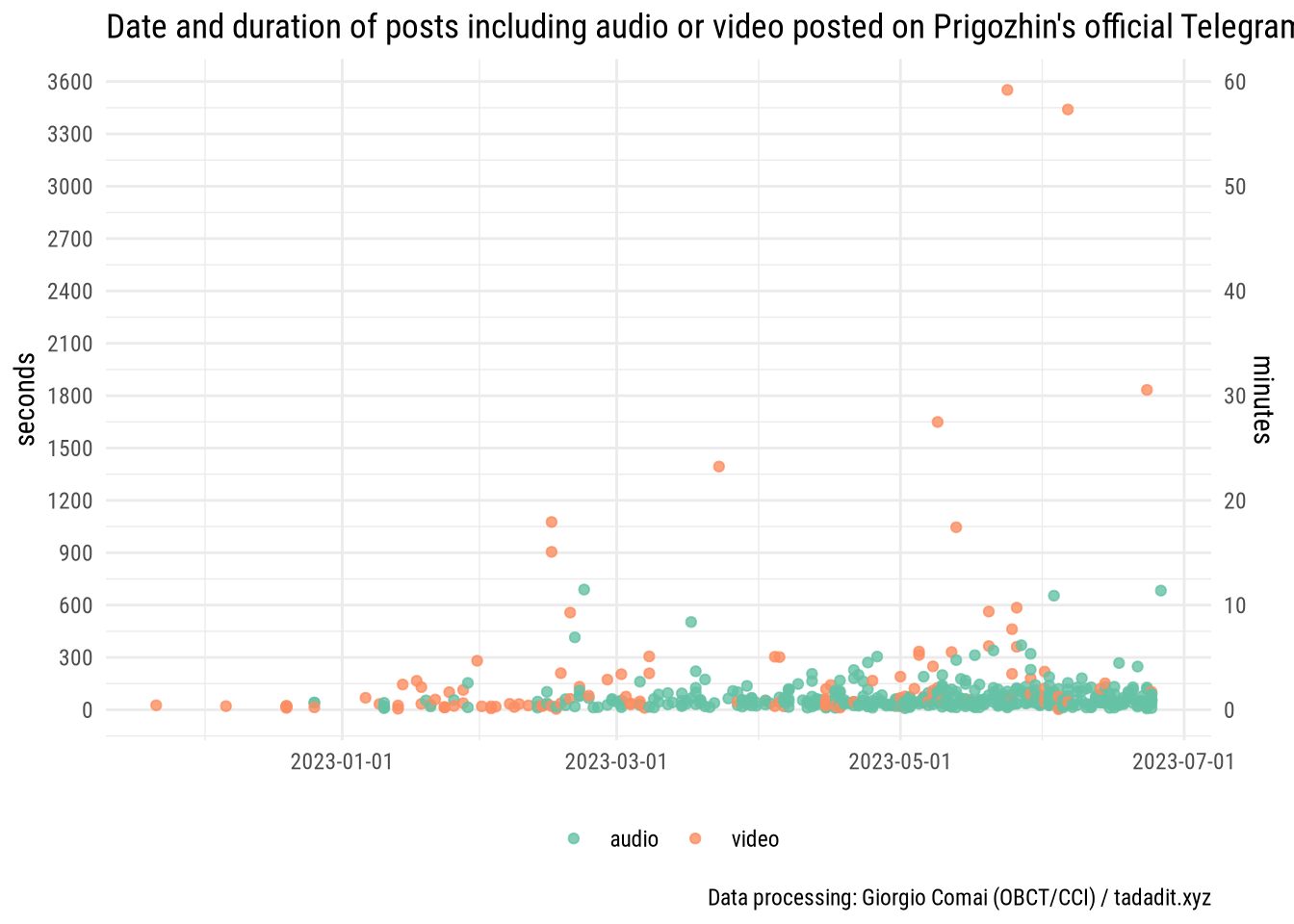

There are both audio and video messages that can be transcribed. Occasional video messages had been posted on the “Prigozhin’s hat” channel for a long time, but audio messages are a relative novelty, with the first one posted on 26 December 2022. In the rest of this post, I will focus on audio messages and Prigozhin’s official channel, as it includes all of the audio posts available.

If we plot the date when each post with either audio or video was posted, and the length of each of these post (i.e. its duration), it’s easy to notice that, a small number of video posts are quite long, up to almost one hour in length, but audio messages are almost invariably shorter than 10 minutes and mostly much shorter.

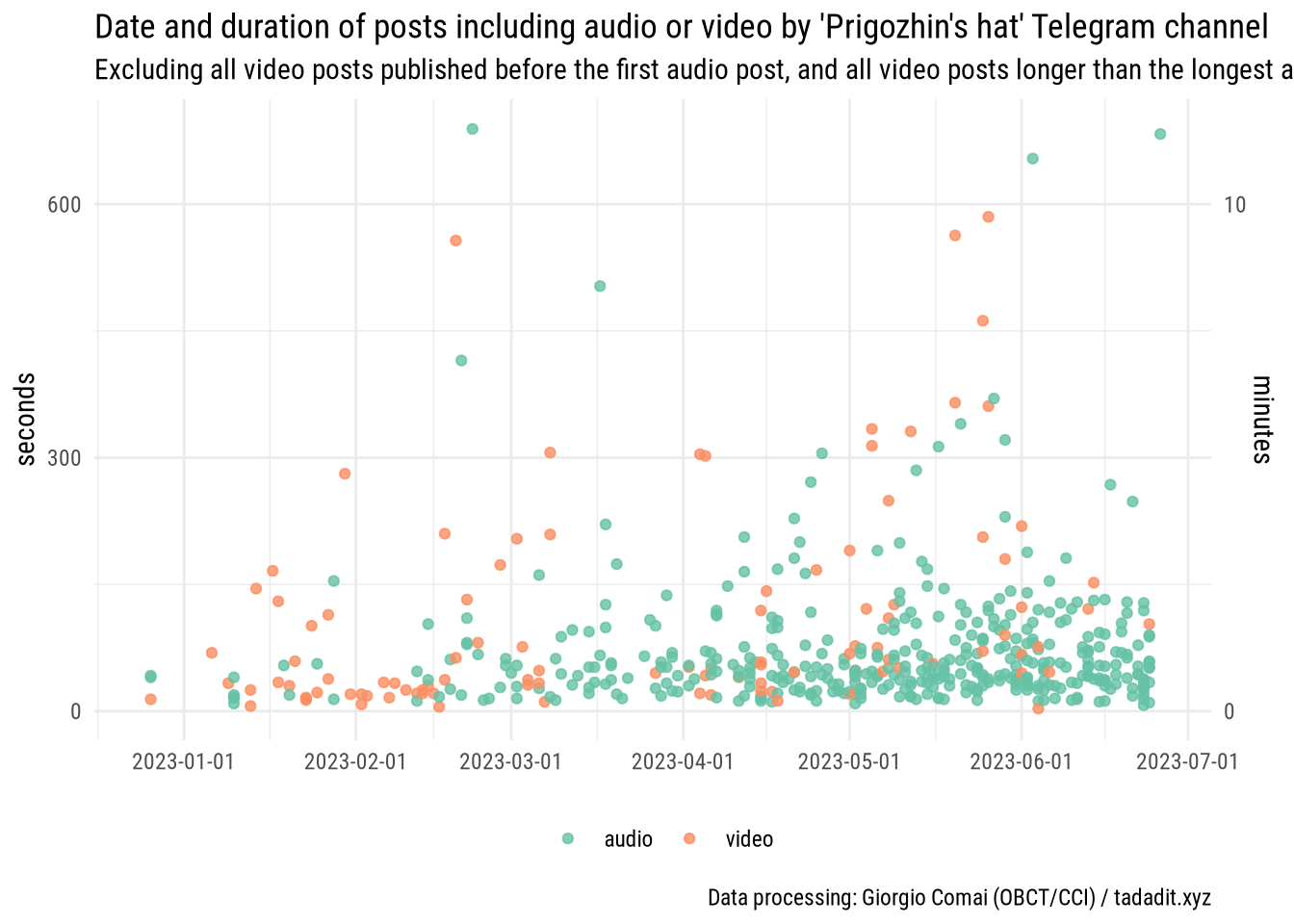

Let’s plot this again, but zooming in on the graph setting the boundaries at the earliest audio message and the longest audio message to see things more clearly. In particular we notice that:

- audio messages start being posted with some regularity around the second half of February 2023

- they stop being posted all of a sudden on a specific day. You can easily spot Prigozhin’s lengthy audio message on the top-right of the graph: Prigozhin’s last message explaining and justifying the end of his mutiny, before effectively going into “radio silence”.

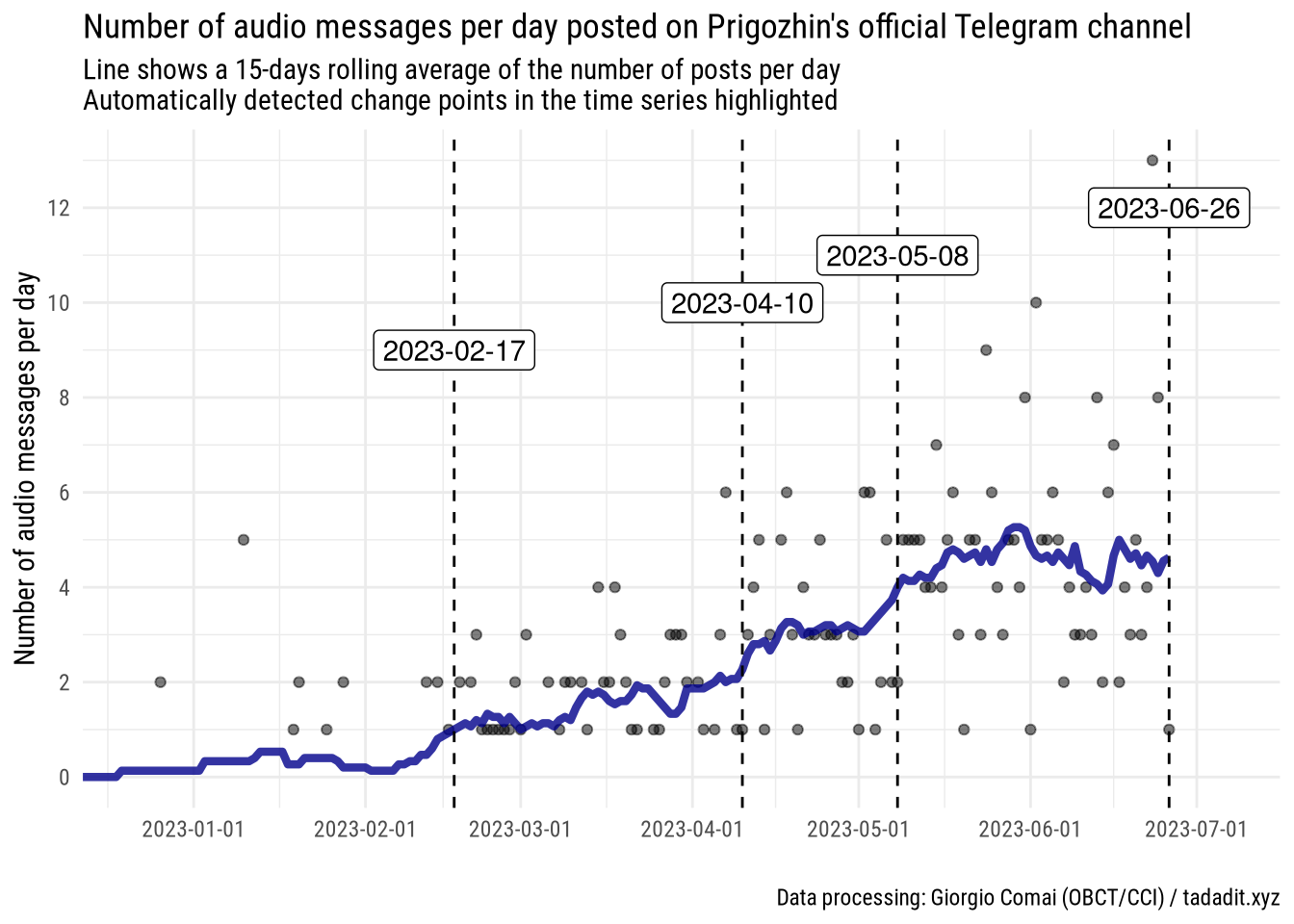

Changes in the frequency of posting

Prigozhin’s audio messages basically identify “Prigozhin’s spring”, from the “battle of Bakhmut” to his “march of justice”. Indeed, just looking at the plain number of audio messages posted each day and using a dedicated function to automatically identify change points in time series, we obtain a visual depiction as well as some key dates marking the escalation.

Without even looking at the contents of these messages, we can tentatively look at these dates and mark some phases in this escalation:

- (before the beginning of this graph) since the day Prigozhin admitted he’s Wagner’s owner and leader on 26 September 2022 to 26 December 2022, when his first audio message was posted

- between then and 19 February 2023, when audio messages were only occasional, but his criticism of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) became more open

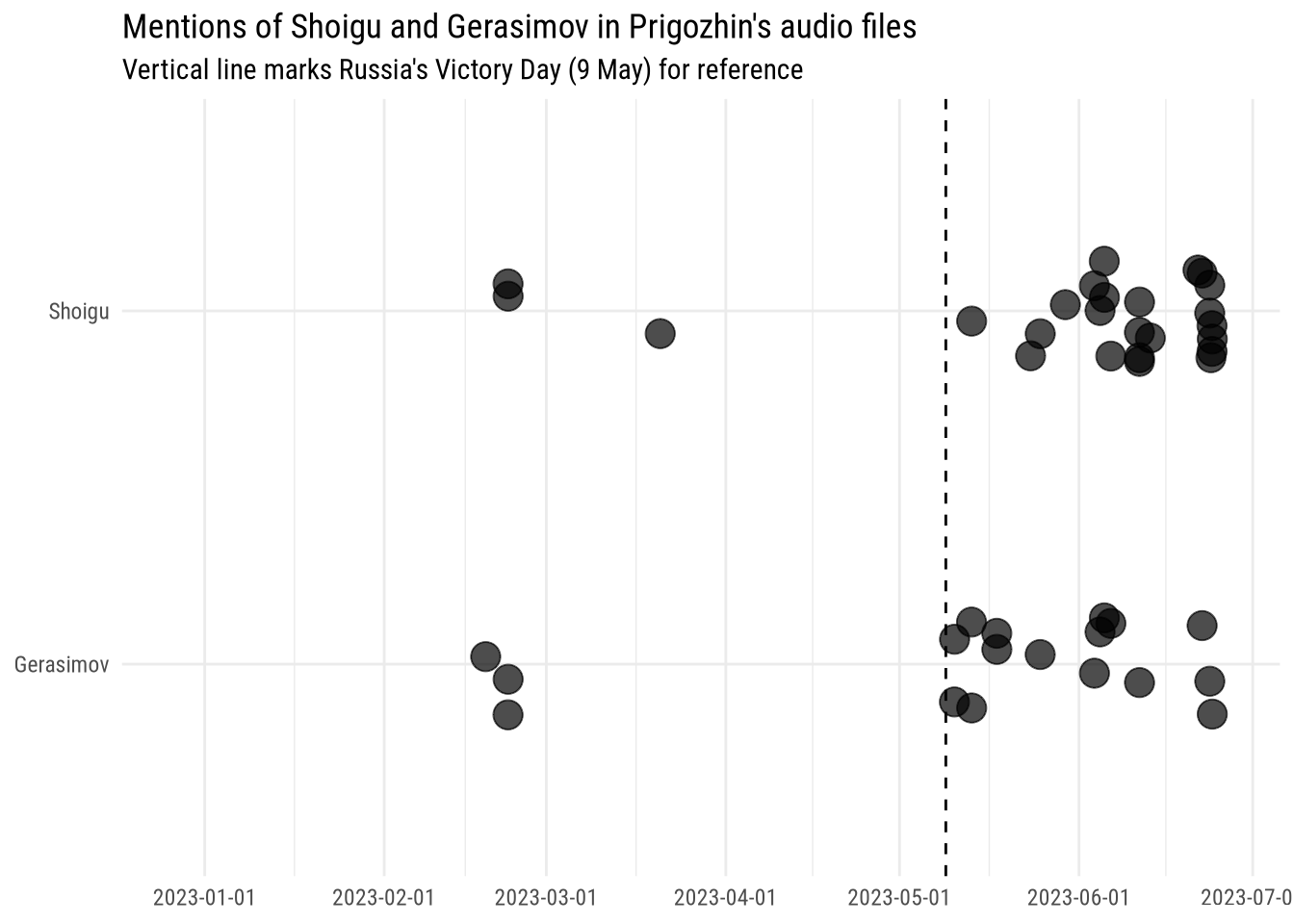

- Since late February, audio messages became more frequent; on 6 March, Prigozhin denounced explicitly the behaviour of the MoD as betrayal, but did not mention by name either Shoigu or Gerasimov

- Starting with April, it became routine for Prigozhin to post three audio messages per day or more

- On 5 May, in a video of himself surrounded by dead bodies, Prigozhin threatened to pull out of Bakhmut. In the weeks that followed, in particular after 9 May (the highly celebrated Victory Day in Russia) his denunciations became more vocal and his audio messages more frequent, averaging over 4 messages per day; it is only at this point that Prigozhin started to openly attack Shoigu and Gerasimov by name

- The high frequency of posts broadly remained in place until the mutiny on 26 June 2023, then they stopped abruptly.

For reference, see the Moscow Times timeline of Prigozhin’s standoff with the Ministry of Defence.

The contents: Prigozhin’s audio messages, transcribed

I include below in tabular format a transcription of all audio messages posted by Prigozhin, first in English, then in Russian. Each line includes a timestamp and a link to the original message. The table can be used for quick searches.

However, for convenience, I am sharing all of the transcribed audio files also as a downloadable dataset, and in a dedicated page where they can be conveniently browsed.

In both cases, be mindful of the errors in both transcription and translation.

- full dataset with all of Prigozhin’s audio messages transcribed is available for download

- all audio files transcribed in Russian and available in a single page

- all audio files transcribed and translated in English and available in a single page (automatic translation, more error-prone)

For reference, here is a graph showing mentions of Minister of Defence Shoigu and and Chief of Staff of the armed forces Gerasimov. It clearly shows how Prigozhin started making their name only after 9 May (Victory Day in Russia). As shown in the graphs above, at the same time, the average number of daily audio messages has also increased. Explicitly mentioning Shoigu and Gerasimov was a clear sign of escalation from Prigozhin’s side. The fact that he was not rebuffed or criticised by the Kremlin at the time was probably instrumental in opening the way for the further escalation that led to Prigozhin’s mutiny on 26 June.

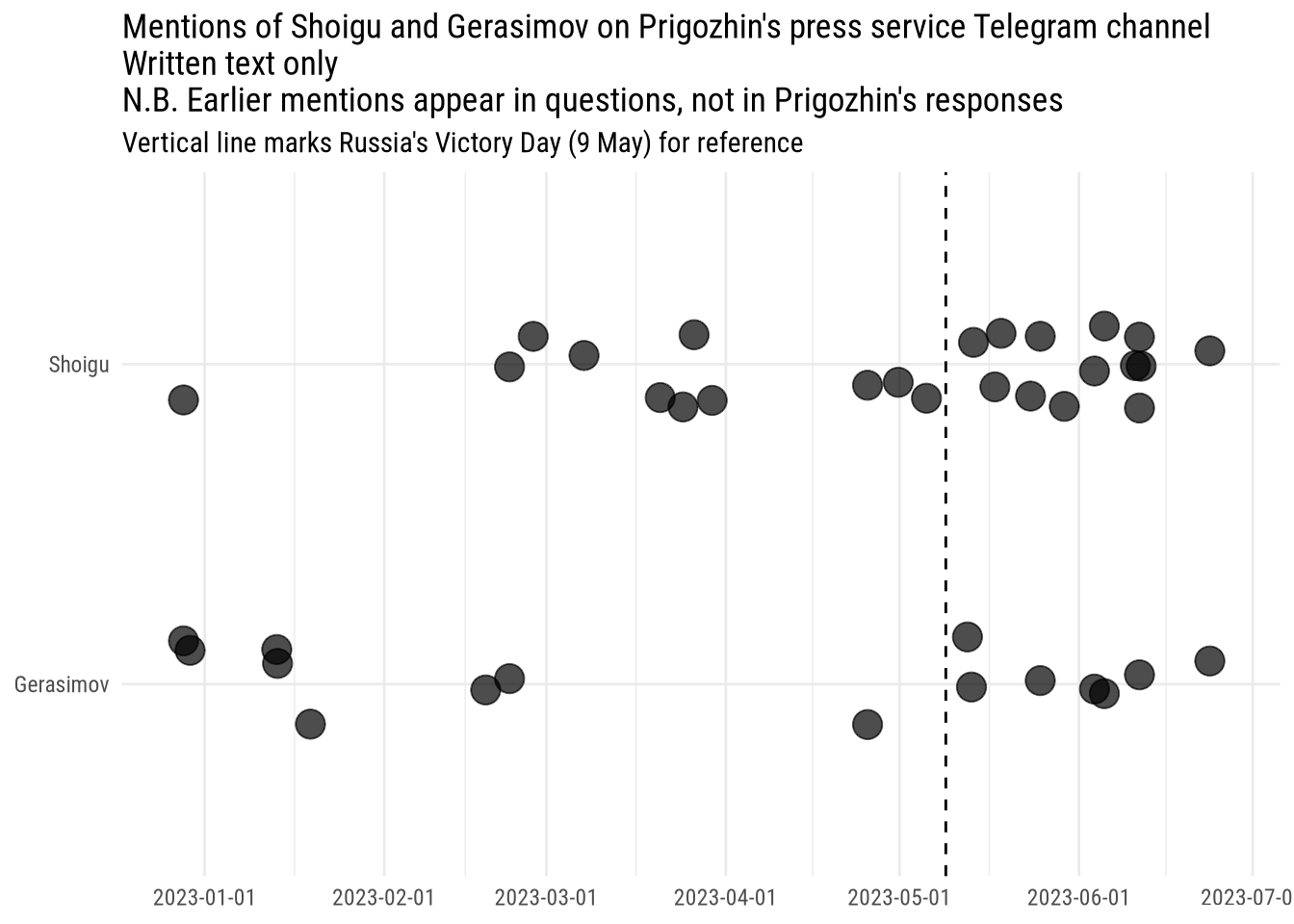

It is worth adding that these messages report Prigozhin’s own words. Text included in the Telegram posts themselves often included both answer and reply, and quite often only the question asked. As it appears from the following graph pointing at mentions of Gerasimov and Shoigu in the text messages of Telegram posts, it easy to notice more earlier mentions. However, they all appear in the questions included in the post: even if journalists were actively asking about Shoigu and Gerasimov, Prigozhin himself never mentioned their name in his responses.

A separate post with further analysis of the contents may follow.

Conclusions

Audio messages, in the case of Prigozhin, and video messages in the case of many other influential voices commenting the war for local audiences in Russia have become an important part of the public conversation about the war, including topics and perspectives that do not appear on traditional media and may be scarcely mentioned in written text.

This post (full code available on this website’s repository) demonstrated how audio messages - including audio messages in Russian, with often less than ideal audio quality and frequent use of slang - can be turned into written text using freely available tools. The speech-to-text process can be run fully offline without relying on third parties and is fully reproducible. It takes however a considerable amount of processing time even on relatively powerful copmuters: if many hours of audio need to be processed, then this is probably not a viable solution at this stage and other options (mostly, relying on commercial vendors) should probably be preferred.

The quality of the transcribed text even using Whisper’s large model is not perfect, but is of surprising accuracy. The text thus generated can easily be parsed to look for specific information or for quantitative analysis, as long as the some issues are kept in consideration, in particular varying spelling for names of people and places (e.g. Shoigu can also be Shaigu). When looking for specific patterns this is mostly rather easy to work around after some tentative exploration.

The quality of the text transcribed and translated in a single step (a feature offered by Whisper) is not as good, and includes some more errors and inaccuracies. Indeed, you may prefer going through Prigozhin’s transcribed messages relying on the Russian version and running it through tools such as Google Translate rather than the automatically transcribed and translated version resulting from Whisper. Yet, the quality is really not that bad, and text can mostly be read and processed, even if being mindful of the fact that there are issues with the text.

Indeed, I recommend reading the transcription of Prigozhin’s audio messages during the mutiny and the weeks that preceded it to see just how unhinged his criticism of Shoigu and Gerasimov had become; if one is allowed to criticise so very publicly the leadership of the army without being rebuffed, he may be (figuratively) excused from thinking that the country’s leadership is really on his side.

As multi-media and multi-format contents become more central to public discourse in Russia and elsewhere, and online spaces where spoken words may be more prominent than written words become more important for public discourse, researchers should expand their analytical toolbox to better account for such sources, even if just in order to define subsets of materials to be analysed qualitatively or explored through complementary approaches.

Footnotes

This applies only to the online news archive of 1tv.ru, which does not include full transcripts of all broadcasts. Even if Prigozhin’s role may have emerged in debates during talk shows, his complete absence from standard news reporting remains telling.↩︎

For those unfamiliar with Telegram channels and curious about where to start, the website tgstat.ru collects statistics about popular Telegram channels in each language.↩︎